The Life of Stephen Meader

“Beneath the light of a single 25-watt bulb in a small room that he rented for $2.00 a week, Stephen Meader began to write a book. Meader had never written a book. He had written for his college newspaper and yearbook, but he had never undertaken a writing project as big as a book. But out of work and wanting very much to be a writer, Meader decided to put the extra time he now had to good use while looking for a job. Not knowing how it was done, he simply started writing the story in longhand. He didn't have an outline, but he had an idea. The book would be a pirate tale for boys.”

From: He Loved to Write Books for Boys By Rick Kelsey

On May 2, 1892, a great writer came into the world. Born the eldest son of Lucy and Walter Meader, a Quaker school teacher, Stephen would toddle beside his father on fascinating visits to see animals in barns and at the zoo almost as soon as he could walk.

When he managed to hold a pencil, little Stephen was drawing animals in adventurous poses - "horses going at full gallop, manes and tails flying and nostrils belching fire." On his fourth birthday, Stephen was given a copy of Rudyard Kipling's, Jungle Book. Filled with interesting characters and exciting adventures, The Jungle Book was the perfect gift for a youngster completely fascinated by animals.

"Father read me the Mowgli stories (from The Jungle Book) until I knew them by heart," Meader recalls in his unpublished memoirs written for his family in 1960, "and before that year (1896) ended (at four years old), I was reading to myself. Books, I had decided, were the most wonderful things in the world."

Stephen Meader

The animals and books that so stimulated his childhood imagination combined with Meader's adult life experiences to create a wealth of creative content for his future novels. Like many of the characters in his adventures, Stephen accepted adult responsibilities at a young age. When Stephen was twelve, his father was passed over for the headmaster position at the Friend's School and quit his teaching job to become a lumberjack in New Hampshire. The elder Meader went into business with a partner who owned a portable sawmill, but the partner "never contributed much in the way of money or effort," Meader recalls. "Father hired and bossed the crews, bought the workhorses and oxen, cruised the timer lots and bargained with their owners."

By the time Meader started high school, his father was working in the woods much of the time. Meader "had to shoulder real responsibilities" for the first time in his life. "I had to be the man of the house, (for his mother, two sisters and brother) keeping the kitchen wood box filled, tending the coal furnace and taking full care of the family horse."

Stephen watched his father "work like a dog," Meader reveals in his memoirs. "If the engine broke down or the log-sled got stuck, he was right there with the men doing more than his share. Most of the French choppers and swampers were pretty wild and got drunk as often as they could find liquor. Father had one showdown with a pair of young huskies, knocking them out one after the other. After that, his orders were obeyed."

When Stephen was around 16 years old, his father's business began to decline. Prices in the lumber market decreased and the elder Meader's partner had stolen most of the cash profits. Walter Meader sold his company, and father and son went to work at the Gonic Manufacturing Company. Walter as an accountant and Stephen as a sweeper during the summer months.

The Meader Family

A bright and gifted scholar, Stephen had been advanced two grades prior to high school. At age 16 Stephen graduated high school second in his class. Because he was so young, his parents decided that he should attend a college preparatory school before attending college, and after a year at the Moses Brown School in Providence, he entered Haverford, a Quaker college near Philadelphia, as one of the youngest members of his class.

While he was at college, Stephen's father continued to work at the Gonic Manufacturing Company supporting his wife and five children and paying for his son's college education on only $30.00 a week. "If I had realized some of these facts, I could certainly have found some job, on or off the campus, to help pay my way. That I didn't has become a source of real regret," Meader states in his unpublished memoirs.

"As it was, I skimped along on my small allowance, hardly ever going to Philadelphia for a play or dinner, as most of my friends did. I washed my own socks and underwear and got my hair cut only once a month, though the cost was then but 25 cents."

During college Stephen studied writing and drawing, wrote for the college newspaper and yearbook and learned how to research articles.

During Meader's senior year, a former upper classroom had offered him a position working in social services in Newark, New Jersey, and after graduating from Haverford in 1913, Meader accepted a position as a Cruelty Officer with the Essex County Children's Aid Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

The work took the young graduate into the lives of families who struggled with poverty, violence and emotional turmoil. Meader describes his work as a Cruelty Officer:

“Many of the complaints came from slatternly mothers against their shiftless husbands, and much of the testimony was pure spite. I had to find out the truth, dictate a report for the files and discuss the case with my boss. Usually we tried to patch up the trouble by getting the parties together.

…I got another call to a white tenement district, where a crazy drunk was threatening his wife and four scrawny children with a butcher knife. I managed to get it away from him and had the neighbors call the police. The man was committed to Caldwell Penitentiary for the traditional "year and a day." His wife was a fat, whining, helpless creature, but I found a job for her scrubbing floors in an office building, and every month or two I visited the dirty two-room flat to make sure the youngsters had enough to eat.”

After college, Meader landed a job as a social worker at the Children's Aid Society. Even though the work was emotionally difficult and demanding, his interactions with those he helped gave him insight into the psychology of human suffering.

In September 1913, Meader's future walked into the shelter where he was working. Betty Hoyt, a slim pretty girl with dark hair and a summer tan, immediately attracted Meader's attention. Apparently, the instant attraction wasn't exactly mutual. "If Betty saw me at all it was as part of the furniture, for she doesn't remember any meeting before my first visit to her home." Meader recalls.

A few weeks after he first caught sight of her, Stephen was invited by a mutual friend to a dinner at Betty's home. This was the first of many visits Stephen would make. But, unfortunately, Betty had many young admirers making it difficult for Stephen to even get a date with her. Stephen persevered, and in February of 1915, Betty and Stephen became engaged.

"I must have won out by sheer persistence, for I am sure some of them had more to offer than I," Meader says in his memoirs. "Yet in one respect I had an edge: I got on famously with her parents. Frank Hoyt and I had long, spirited arguments about books and writers. And he agreed with my own feeling that I would be better off in literary endeavor than in social work"

Meader had left the Children's Aid Society and had begun working for the Big Brother Movement. By the fall of 1915, funds for the organization were so low, that Meader found himself working at the loathsome task of having to raise money to pay for his own salary.

During that same fall, in a visit to a public library, Meader came across material on Carolina Pirates. The idea of The Black Buccaneer in which a young boy is taken hostage by the real life pirate Stede Bonnet, began to take shape in Meader's imagination. With $300 in savings, Meader quit his job and dedicated himself to his writing. Kelsey describes Meader's sacrifices:

To cut down on expenses, he moved from a boarding house to the cheaper room and resolved to live on $1.00 a day for meals. Doughnuts and coffee for breakfast cost: 10-15 cents. For lunch, Meader found a bargain meal of bread and a big dish of mashed turnips for 20 cents. And at dinnertime he would splurge with a cafeteria meal for 70 cents.

If suffering and sacrifice were requirements for artistic or literary success, then the mashed turnips might have fulfilled those conditions. Never again would Meader eat turnips.

While writing, Meader sent out job application letters to book and magazine publishers, and in 1916, he set aside work on his own novel to accept a job at $20.00 a week with a Chicago publishing house. His job description called for him to write publicity for the publisher's book line and to attend to "other tasks". Meader describes one responsibility of the position:

One of my less literary tasks was to get the firm's production man home safely after work. He was a rabbit-faced old character who knew printing and binding but had an addiction to rye whiskey. And though he lived only half a dozen blocks away, he insisted on stopping at every saloon we passed for "just one shot." The usual score was about 12 jiggers by the time I got him to his door.

In May of 1916, on the same day he finished paying off an engagement ring for Betty, Meader received a letter offering him a job at the Circulation Department of the Curtis Publishing company in Philadelphia. As a correspondent for the Sales Division he would be responsible for corresponding with young boys who sold coupons for the Post, Ladies Home Journal and Country Gentlemen magazines.

The job would take Meader back home to Philadelphia, and he would be earning $25.00 a week. Betty and Stephen decided it was time to get married. On December 16, 1916, the couple moved into their first rental home described by Meader:

We set up housekeeping as best we could. Our furniture was cheap and meager, and the house was dark and hard to heat. We did practically no entertaining, partly because we had so few friends, partly because we couldn't afford it.

In 1917, the United States was involved in World War I, but because Betty was pregnant with their first child and neither her family nor Meader's family could support his wife and expected infant, Meader was given a 4-A classification.

Meader had already received two promotions at Curtis Publishing and was now working as Editor of the Sales Division house publications. The raise in salary his new position offered enabled the couple to move into a nicer apartment in a stone mansion in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

On January 10, 1918, their first son, Stephen, Jr. was born and brought home to their new apartment. By the fall of 1918, Betty was expecting their second child, and Meader, in an effort to generate more income, went back to work on The Black Buccaneer. According to Kesley, the young family experienced some difficult times during the winter of 1919.

As another winter started, conditions worsened. Temperatures were constantly dropping to unbearably cold levels, and an influenza epidemic was spreading throughout the area. The epidemic was fatal to many, especially pregnant women. In February 1919, Betty caught the disease. "It was touch and go," Meader said. "Somehow she pulled through, and Jane was born safely on the 23rd of March. Thrilled at having a girl child, I wrote a little poem called 'To a March Baby,' which was published in the Philadelphia Evening Ledger."

Meader completed The Black Buccaneer later in 1919 and forwarded it to Morley, who was now working at Doubleday's editorial department, for his opinion.

When I had finished it about 1919, I sent it to Christopher Morely, my good friend and said, 'Chris, I've written a book. It's just a pirate story for boys. I wish you would read it.'

I didn't hear from him for about three weeks. He finally wrote back and said, 'Steve, I like your story. Since you're a brand new author, I am sending it to a brand new publisher, a man named Alfred Harcourt, who is leaving Henry Holt and starting his own business with a man by the name of Brace.'

Harcourt, Brace and Howe published The Black Buccaneer in 1920 as their first juvenile publication. Later editions of Meader's work would feature illustrations by Mead Schaeffer and Edward Shenton, but all illustrations in the original edition of The Black Buccaneer were drawn by Meader himself.

Stephen Meader

1920 was a good year for Meader. His first book had been published, and he was now working as Art Editor on The Country Gentlemen, a weekly Curtis publication. 'I had to lay it out, page by page, working three or four weeks ahead," Meader explains. "The covers were also my responsibility. Norman Rockwell did about a quarter of them; others were by Charles Livingston Bull and other well-known artists. I frequently visited them to discuss future paintings."

In January 1921, Meader submitted a short story, "Son of the Blizzard," a story about a horse, to the editor of The Country Gentlemen. With several horse stories on file, the editor sent Meader's story on to a competitor's publication which purchased it for $250.00. Cyris Curtis, head of Curtis Publishing, was incensed that Meader had sold the story out of house and decided to let Meader go. Even though the editor of The Country Gentlemen explained that Meader had initially offered it free to the Curtis publication, Cyris Curtis insisted on firing Meader.

"That was the first and only time I was ever fired from a job, and it hurt," Meader recalled. "We were in a minor depression in 1921. Nobody seemed to be hiring. And to make things worse, we had just moved to a new row house on Ogontz Avenue, which we were buying."

Meader finally landed a part-time morning job as an assistant art director for an advertising agency in New York, and leaving his family at home in Philadelphia, lived with his in-laws in Montclair while commuting each morning to work. His morning part-time position did offer him afternoons to spend on his second adventure novel, Down the Big River, which was published in 1934.

With another baby on the way, Meader wanted very much to find work near home. Fortunately another old college friend, Hans Froelicher, helped Meader secure a position with the Holmes Press. A third child, John, was born in 1921, and in 1922, the family moved to Moorestown, New Jersey. From 1921 to 1927, Meader wrote his own books while working as a copywriter and lay out editor for Holmes Press.

A fourth girl, Peggy Lou, was born in 1926, and in 1927, the year after her birth, Meader applied for and accepted a job as a copy writer and copy director with N.W. Ayer & Son, a Philadelphia advertising firm. Meader describes why the job was a perfect fit for the author's lifestyle:

N.W. Ayer and Son was the kind of place where there were few desperate emergencies, except once or twice where I got into one of these things where I could work all night trying to save an account. We went home at five 'o-clock. I would play with the kids and by half-past eight or nine I was ready to write. I took all my advertising out of my head and was eager to get on with a story I was doing. It was fun.

Meader wrote all of his novels in longhand on a lapboard. His son, John, recalls evenings at home with his author/father:

His powers of concentration were remarkable. He would sit in the living room writing while my brother, two sisters and I were in and out of the room playing with the dog, listening to the radio, or asking him questions about homework.

When the handwritten version of a story was completed, Meader would turn the novel over to a professional typist. Meader's wife would then proofread the story before sending it on to the publisher. Betty would proofread and knit at the same time. Each novel took approximately five to seven months to write and research. Typing and proofreading required another month or more. During this time, an illustrator would consult with Meader on the book's illustrations.

In 1928 Longshanks, his third book, was published, and in 1930, his fourth book and best seller, Red Horse Hill was released. The extra income derived from his work as a novelist was extremely helpful to the Meader family especially during the Depression of 1929 when Meader's work week was decreased from five to four days a week and his salary cut 20 percent. "His books sold well because the publisher was eager to take all that he wrote. The extra income was certainly an important plus because we grew up in the big Depression and things were tough," John Meader recalls.

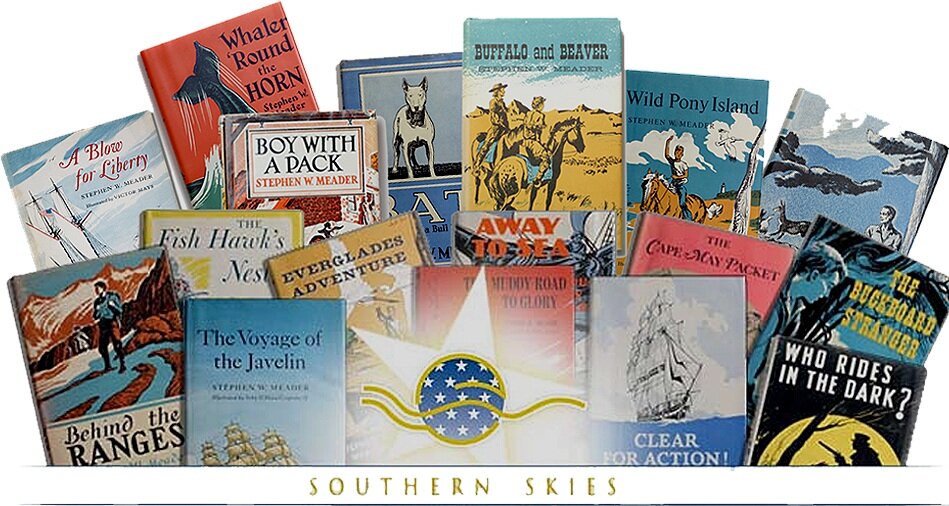

Meader continued working in advertising at N.W. Ayer and Son until his retirement in 1957. During those years he wrote 26 novels. After his retirement, he continued to write one book a year, completing his last novel, The Cape May Packet, at age 77 in 1969.

In 1962, his wife Betty died, and in 1963 Meader remarried Patience R. Ludlam, the widow of his college roommate Jesse Ludlam.

A widely popular author during his time, Meader's new releases were reported in the local press, and his novels brought him wide spread recognition and admiration. His son, John, describes his father's popularity.

Around here he was very popular as an author, and I think well recognized and appreciated everywhere. He received a great deal of fan mail and frequently was invited to speak at schools and libraries. Fans often asked what it took to become a writer. His answer generally was 'stick to it and write, write, write.' His advice to budding authors was to write in simple terms. Don't get carried away with big words and long, involved sentences.

His popularity extended to the military, and in 1955, two Air Force captains visited and asked him to write about a young jet fighter pilot. The result was Sabre Pilot published in 1956 with a dedication to "My two flying sons - Stephen Warren Meader, Jr. and John Hoyt Meader."

By the time Meader finished his last novel in 1969, the world of the 1970's youth involved sex, drugs and more contemporary subject matter. Harcourt indicated that they would not be publishing any additional Meader novels, and Meader decided that he didn't really want to try to change his style to match the times. According to his son John, "He did some writing for the Cape May Historical Society, but that was about all. By then, he was well into his seventies and content to relax and read."

At the age of 80, Meader and his wife, Patience, were interviewed in their Cape May Courthouse, New Jersey, home by Robert Gallagher for his Graduate paper, Stephen W. Meader, A Biography. In one interview with Gallagher, Meader expressed his personal feelings about his body of work:

"I think I developed the idea, after publishing about 20 books, that I had a mission and that mission was to cover all of America, all of the periods that were adventurous and romantic and hadn't been written about and all the, to me, fascinating places.

If you look over that list (of books), they cover the United States from Maine to Hawaii, Puget Sound to Florida. The bulk of the concept I have never fulfilled quite, but it's there. What I wanted to do is give children from sixth grade on a chance to open their minds to the bigness of the country and the richness of its history and that has been my aim. I think a lot of kids have developed some of that feel. They have enlarged their horizons. If I have done anything that is worthwhile in this life, that is it."

Stephen W. Meader died on July 18, 1977 of natural causes.

*Material for this biography was derived from the article, "He Loved To Write Books for Boys," by Rick Kelsey, freelance writer and children's series books collector.